The real success story beneath London is, of course, the Underground. Aside from drainage, the opening of the Metropolitan line between Paddington and Farringdon in 1863 gave rise, arguably, to the most common reason to puncture the earth below our cities: mass rapid transit.

Although the northern cities of Liverpool and Manchester had a head start on building railways, England’s capital wasn’t far behind.

By the 1840s, London was encircled by railway termini, but the biggest obstacle to crossing the great city was its historic centre: Parliament itself legislated against simply smashing up the existing urban area in order to push new railways further into central London.

City solicitor Charles Pearson suggested connecting the disparate terminals by placing a new line below the streets in a 6-km (3.7-mile) tunnel.

LOCAL ADVERTISING

Construction – complete by the end of 1862 – was constrained by the locomotive power of the day, and trains were pulled by steam-powered engines. Despite ingenious attempts to recycle their exhausts, they filled the tunnels with smoke and fumes, so they had to be built in relatively shallow trenches with plenty of gaps for letting out gases.

Despite dire warnings of asphyxiation in the sooty atmosphere, the initial line was so successful it was soon extended and spurned the development of additional tunnelled railway lines.

The Metropolitan District Railway filled the space above Bazalgette’s Victoria Embankment sewer, leading to the completion of a full circular route by 1884. Within a few short years, following the discovery of electricity, it became possible to power trains using this newfangled source of energy. The first London tunnel to benefit from it was the City and South London Railway, which opened in 1890.

It also became feasible to bore deeper tunnels than the subsurface lines that had skirted built-up London to this date. Built using this method, the Central London Railway was opened in 1900. Known as ‘the Tube’, a name that is now commonly used for the whole network, it ran between the capital’s busiest shopping areas around Oxford Street and the City, near St. Paul’s Cathedral. The bright, white-tiled platforms and cheap ‘tuppenny’ fare increased interest in providing more lines.

Three additional routes, the deep-level tubes that would penetrate and properly serve the West End, opened between 1906 and 1908 and eventually became known as the Bakerloo, Northern and Piccadilly Lines. The combined tunnelled rail services were collectively named the Underground from 1907.

Such advances in engineering spurned similar ventures in Budapest (1896), Glasgow (1896), Paris (1900), Berlin (1902) and New York (1904). Following a spurt of building in the 1930s and another just after the Second World War, construction on the Victoria Line began in the 1960s and the Jubilee Line in the 1990s.

Underground construction was back on the agenda in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, with the Crossrail project that began in 2009. Boring 21km (13 miles) of new tunnels beneath London, the Elizabeth Line, as it is named, carries mainline-sized trains from both the eastern and western suburbs and is comparable to the Paris RER system.

Spotlight on Piccadilly Circus Station

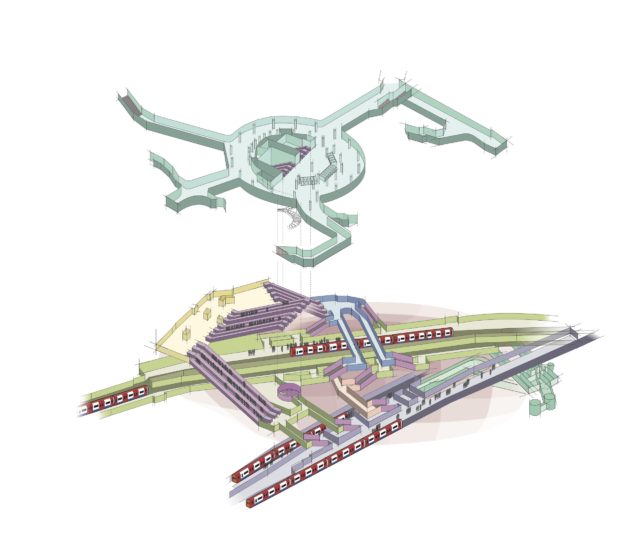

Most pedestrians passing through London’s iconic Piccadilly Circus probably spend more time being mesmerized by the bright LED advertising screens than thinking about what lies beneath their feet, but under Eros is a tangled web of tunnels, both in constant use, and abandoned.

When Piccadilly Circus tube station first opened in 1906, the only way between the street and the platforms 30m (98ft) below was by lift. By the early 1920s up to 18 million passengers were squeezing into the elevators, so London Transport decided to build a new sub-surface ticket hall with eleven escalators leading to the Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines.

Architect Charles Holden began work in 1925 and builders John Mowelm completed the job in three years, while the Eros statue was moved to a temporary home on the Embankment. The resulting circulating area in biscuit coloured travertine marble and art deco pillars and uplighters was described as a ‘masterpiece of opulence and chic’. The lifts and their access tunnels to the platforms were closed in 1929 but remain in ghostly empty silence beneath one of the capital’s busiest subterranean spaces.

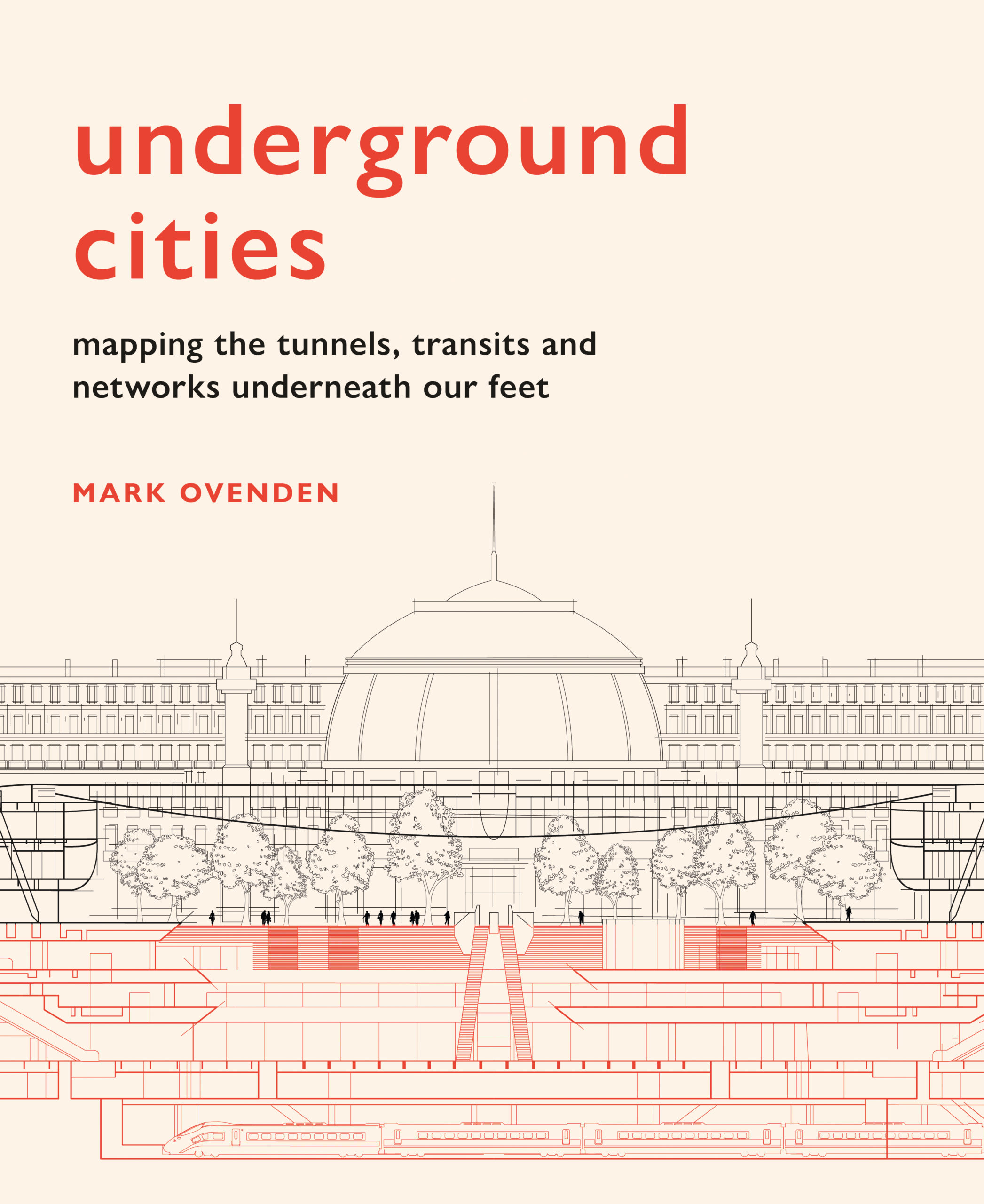

This is an extract from Underground Cities by Mark Ovenden is published on 22nd September on Frances Lincoln, priced £30 hardback available here

Please support us if you can

With the sad demise of our free monthly print titles across London last summer due to advertising revenues in freefall, we now need your support more than ever. Every contribution, however big or small, is invaluable in helping the costs of running our websites and the time invested in the research and writing of the articles published. Please consider supporting us here – for less than the price of a coffee. Thank you.