My new book explores the distinctive place of Fitzrovia and its working people in the story of London, at a time of enormous change between 1900 and the end of the Second World War.

It is the first work to be wholly focused on the daily activities and experiences of Fitzrovia’s working population rather than on the select group of artists and writers known as the ‘Fitzrovians’ that famously included Dylan Thomas.

Situated on the north side of Oxford Street – the other side of the street from Soho, to the south – it was home to my mother’s family of Jewish tailors before the Second World War. They were foreign immigrants, like many of the area’s working people who came from all over Europe and beyond. This is one important reason why Fitzrovia has always fascinated me.

It was, and is, many sided. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it was often publicly characterised by dark visions of an unruly nameless borderland contaminated with crime, deceit, poverty and sickness. However, other views have revealed its vigour and ability to triumphantly harness change and reinvent itself.

LOCAL ADVERTISING

Fitzrovia never really fitted into the affluent West End, although this is now changing as it becomes ever more gentrified. At the same time, it adjoins the West End in ways that make its exact boundaries hard to determine. Its edge-land quality, and the constant sense of movement conjured up by its changing populations, and its fluid borders, generated a sense of excitement in me from when I was a child.

Fitzrovia has always seemed, to some extent, unknown territory. It was connected to my feeling that my family’s history was a bit mysterious, its origins being in places like Poland and Belarus, whose own boundaries, I discovered, had shifted over the years and centuries. From a young age I’ve been wondering and imagining what daily life in pre-war Fitzrovia was like, particularly for its many immigrant families, like my mother’s family.

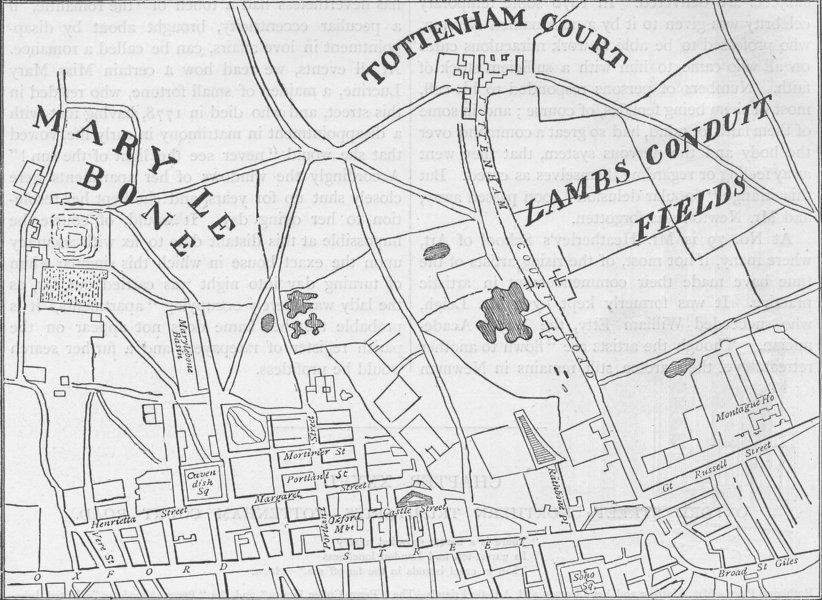

This family connection is one important reason why the book focuses on the period 1900–50. My matrilineal ties to Fitzrovia – ‘around Tottenham Court Road’, as my mother called it – began and ended within this timespan. But the other compelling reason for my interest in this historical period is that it brought major economic and social changes which affected the area in numerous ways.

Indeed, there’s a good case for saying that the years 1900–50, momentous as they were for those who lived and worked on ‘the other side’ of Oxford Street, were the most interesting historically for Fitzrovia.

Why call the book The Other Side of Oxford Street? The reason is, I was intrigued by finding out that some West End Jews in Soho referred to Fitzrovia’s Jews as coming from ‘the Other Side’ of Oxford Street. In fact, the idea that Oxford Street had an ‘other side’ in communal terms, began with local Jewish communities. It immediately begs the question, ‘the other side of what?’ There are several possible answers.

For those Jews who lived in Soho, south of Oxford Street, ‘the Other Side’ meant the area on the north side of Oxford Street: somewhere a little beyond their centrally located West End habitation. But the Jewish residents of Fitzrovia, in their turn, thought of Soho as ‘the Other Side’. These groups of early twentieth-century Jews, separated by the barrier of Oxford Street, which was Fitzrovia’s southern boundary, did in fact think of themselves as separate communities, and it was a matter of note when a member of one community married someone in the other community. Some of their comments about, and explanations of, this division between almost identical communities appear in the book.

This idiosyncratic sense of place also indicates a perception of separateness, shared by many other Londoners, between Fitzrovia and the West End. However, Oxford Street’s Fitzrovia border hasn’t always been fixed in people’s minds, since the label ‘Soho’ has also embraced Fitzrovia at times in the past. These shifting relationships between the two begin to illustrate the difficulty of firmly anchoring Fitzrovia within London, either geographically or imaginatively.

And there are yet more ‘Other Sides’ to Fitzrovia. Euston Road, lying at the opposite end of Tottenham Court Road, forms the northern boundary. It is a formidable barrier that maintains Fitzrovia’s place in Zone One of central London; but it is not an unchallengeable barrier. Euston Road was originally constructed in the mid-eighteenth century to define the northern edge of London itself; so, from here, the ‘Other Side’ takes on another meaning.

To someone living north of the Euston Road, in Camden Town, King’s Cross or Kentish Town, which were all outlying districts of London in the nineteenth century, ‘the Other Side’ of the Euston Road would signify somewhere definitively belonging to the centre of the city, with all the changes in status that entailed.

From this perspective, Fitzrovia, in the city centre but not central in the same way as the West End and Mayfair, still remained ambiguous.