Between 1850 and 1900 the two salient facts in London’s story were the population explosion and the transport revolution. In two generations the head-count of Londoners leapt from two to six million, while buses, railways and the Underground completely changed the rhythm of people’s lives.

You no longer lived a few steps from your place of work, but could criss-cross the capital at will. The offspring of these twin revolutions was suburbia – the horizontal sprawl of housing which felt interminable if you walked through it, but which the trains clattered through in half an hour or so.

Suburbia dispersed the exploding population, and the railways made suburbia possible. In every direction, north, east, south and west, as fast as the builders could work, the new tenants moved in. Miles and miles of new streets and new houses appeared, each someone’s personal domain, but all very nearly identical, whose inhabitants migrated every morning to work in the old, historical London, then returned each evening to their private dormitory.

The great characteristic of urban life became incessant movement in time and space, movement between different modes of life: day and night, work and leisure, public and private, weekday and weekend, office and home, city and suburb.

LOCAL ADVERTISING

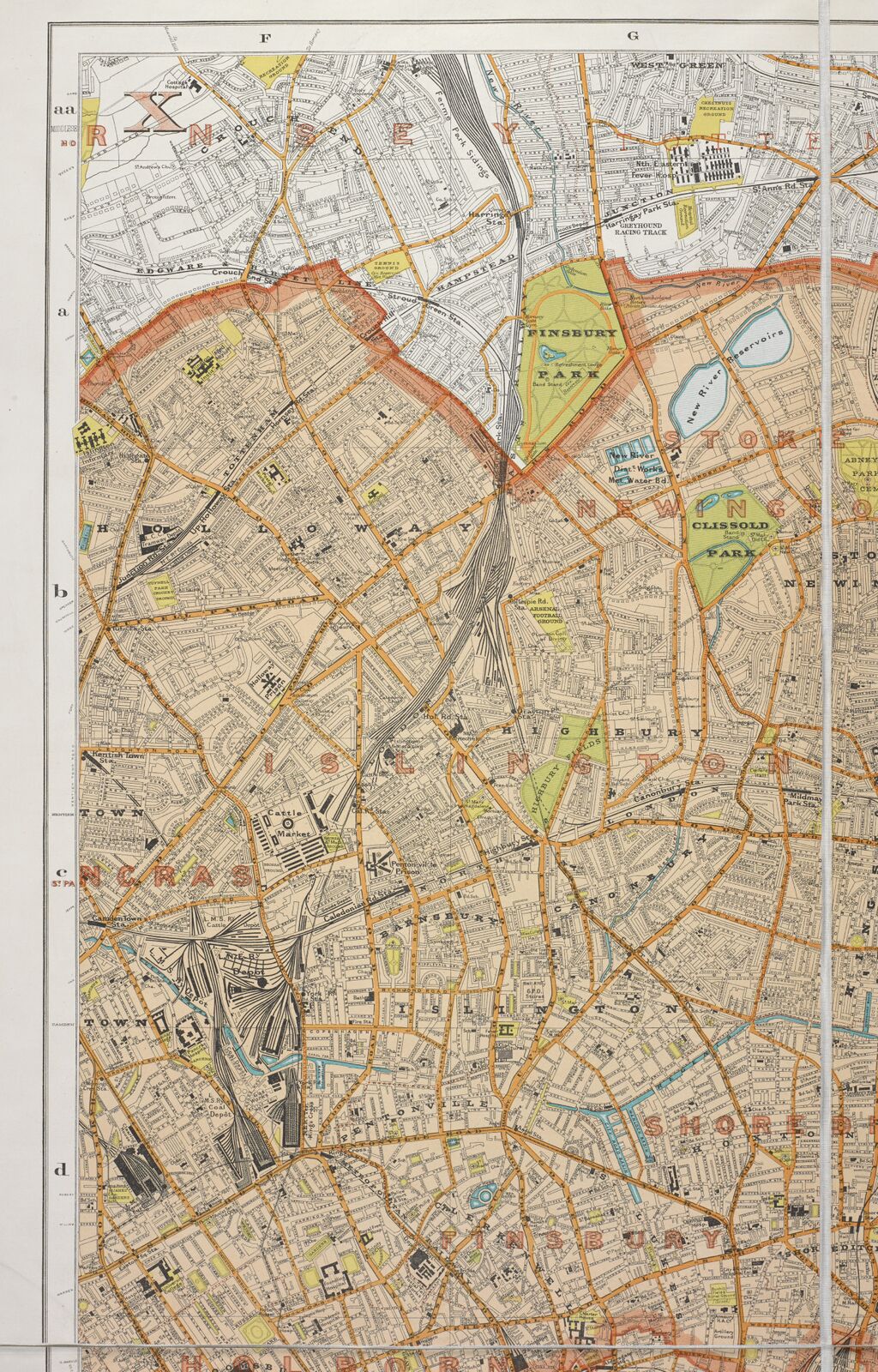

In reality, the suburbs were far from featureless. Those on the northern or southern heights, for example, were built precisely because their setting was attractive – places such as Hornsey, Highbury, Denmark Hill and Wimbledon. There were really several gradations of suburb. The spacious, leafy, semi-rural enclaves whose names often ended in Hill or Green or Park were resolutely middle class, and at least five or six miles from the City.

Before these were reached, there was an inner ring of mixed-class suburbs, which obliterated the older villages, especially those north and east of the City, in Middlesex and Essex: Islington, Holloway, Tottenham, Hackney, Stratford, Leyton and Walthamstow. From these places clerks could reach the City and labourers could reach their warehouses and workshops by the cheap early morning trains.

The Great Northern Line from King’s Cross and the Great Eastern from Liverpool Street effectively created all these northern suburbs, from Camden Town to Enfield, from Hackney to Ilford. People in their thousands exchanged the overcrowded warrens of Stepney and Shoreditch for the terraced streets of East Ham or Tottenham, and the same pattern was repeated as south London was built over from Brixton to Croydon, and west London from Paddington to Harrow.

As early as 1720, Defoe had written that the road from the City almost as far as Enfield appeared to be one continuous street, lined with cottages and taverns. Yet, until the coming of the railway more than a century later, the hinterground was still entirely rural – farms, woods, heaths, ponds and green lanes.

The new era of suburban transport was marked symbolically in 1864 when the old tolls and turnpikes in and out of London were abolished, for they belonged to the vanished age of horses and coaches. By 1900 the green lanes had long disappeared beneath the endless ranks of houses, punctuated by shops, pubs and two fortress-like prisons.

A few Holloway streets remained staid and respectable, the sort made famous as Pooter-land in The Diary of a Nobody, but this was also the land of music halls, gaslight, prostitutes and murder. The Crippen case in Hilldrop Crescent was the most sensational crime of the age, involving jealousy, poisoning, a dismembered body in the cellar and an attempted escape by ship to America; it sank deep into the nation’s folkmemory.

Other murderers of suburban north London included Frederick Seddon and George Joseph Smith, who killed to gain inheritance or insurance money, and Mary Pearcy, the blood-stained pram murderer. All these cases sprang from ‘malice domestic’, and seemed to symbolise the hidden lives that were lived behind the respectable façades.

Where Holloway bordered Tottenham lay the Seven Sisters Road, subject of a whole mythology among Edwardian Londoners. Its cheap lodging-houses were home to thieves, fences, prostitutes, drunkards and gamblers. One side street at its western end, Campbell Road, colloquially known as ‘The Bunk’, was legendary as the worst street in London, inhabited by an underclass living at war with society.

Suburbia may have been like a frontier, constantly expanding to give people the chance to escape urban pressures, but obviously a whole class was being left behind, and these inner mixed-class suburbs could easily degenerate into hopeless slums. It is hard to imagine that Housman wrote A Shropshire Lad while he was a lonely clerk living a stone’s throw from the Seven Sisters Road.