Diaries and journals as we know them now have been with us since at least the 16th century. But it wasn’t until 1812 that the stationer John Letts first began selling a yearly almanack from his shop at the Royal Exchange in London – at that time home to numerous booksellers and coffeehouses and an area previously haunted by Pepys.

The Letts Diary was an immediate success, attracting such devoted users as William Makepeace Thackeray who favoured the ‘three shillings cloth boards’ No 12 model, and continues to be published in a multitude of formats to this day.

I’ve never really kept a diary. But I am an inveterate reader of other people’s. For me, the appeal has always been their immediacy and intimacy. That unique sense of being addressed directly, and sometimes extremely candidly, by someone, perhaps from an age other than our own, is intensely seductive.

As a historian, and author of books on vinyl records and the British seaside, diaries are also where I go to try and find as instantaneous or unvarnished a reaction to events as possible.

LOCAL ADVERTISING

Diaries are, of course, often far from authoritative and have no commitment to tell the truth or record incidents accurately. They are by their very nature subjective, and so subject to the egos, whims and biases of their writers. But personal diaries often catch things that more official sources fail to notice or simply neglect to mention.

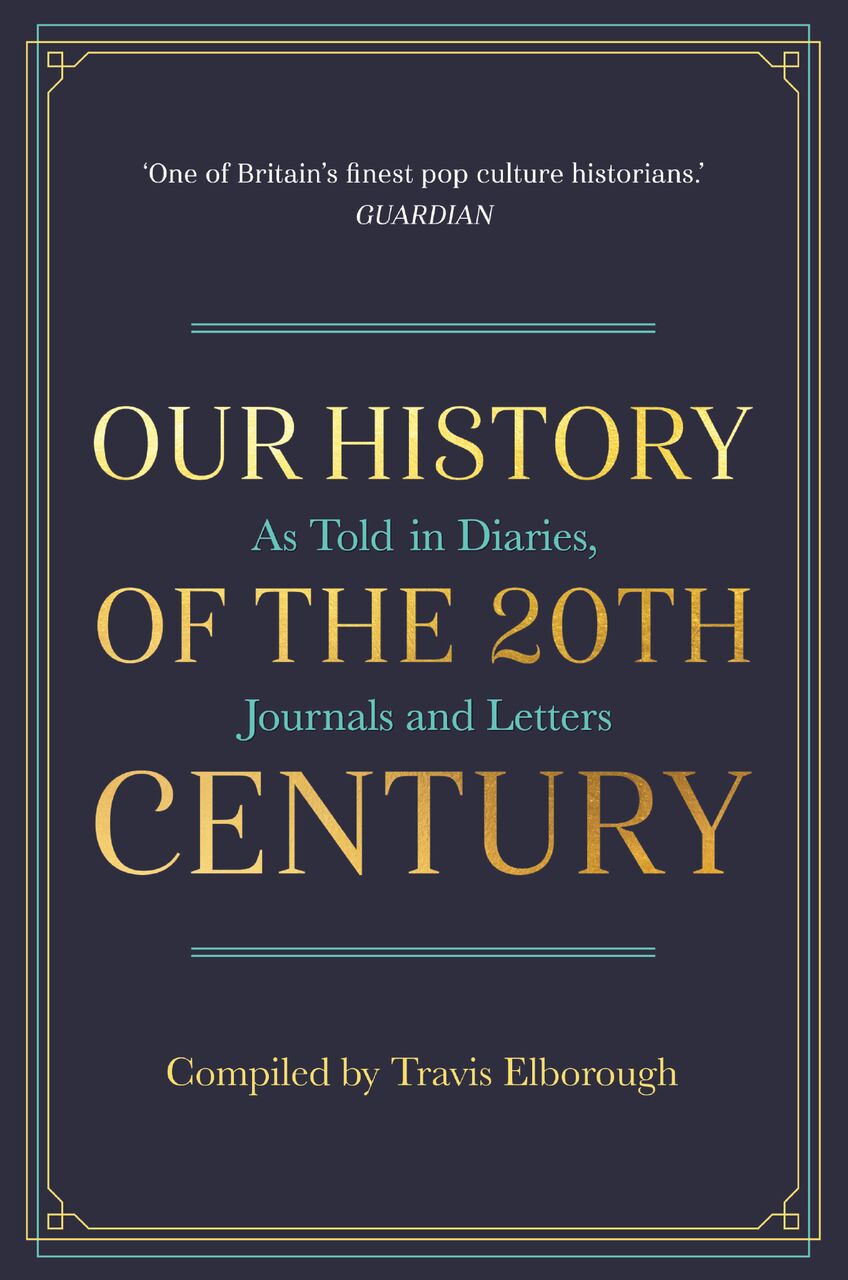

My latest anthology, Our History of the 20th Century, uses extracts from over a hundred different diarists, both the great and the good and the completely obscure, to present a kind of top down and bottom up account of Britain during the last century.

My diarists range from politicians, heads of state, novelists, playwrights and celebrities to ordinary people and the largely unknown and unsung contributors to the Mass Observation Project.

By assembling a range of differing voices, and by shifting between the epoch-making and the personal or domestic, I wanted to create an impressionist portrait of those days – and offer an experience for the reader that was closest to eaves-dropping as anything else.

The book moves chronologically from 1900 to the millennium, taking us from a Britain ruled by Queen Victoria to the one guided by a (then) still immensely popular Tony Blair. The Britain of 1900 is a place mostly powered by steam and horse and its maps are tinged pink with the territories of the Empire. The Britain we finally reach in 1999 is at one (just about) with the hyperlink and the information superhighway, its economy grateful for the pink pound.

Along the way there are homefront reactions to the century’s two world wars, as well as impressions of the Suffragettes’ Campaign for Votes for Women, the General Strike, the Wall Street Crash, rationing and austerity, the Festival of Britain, mods and rockers fighting at the seaside, the 1966 World Cup, man landing on the moon, the three-day week, punk rock, the election of Margaret Thatcher, the Brixton riots, the miners’ strike, the arrival of AIDS, the Poll Tax protests, the fall of the Berlin Wall and celebrations at the Millennium Dome.

There are sightings of new technological innovations from motor cars to dial-up modems. Frances Partridge, for example, finds a television set ‘a little fussy square of confusion and noise’; Joe Orton surmises that Polaroid cameras could be good for home-made porn and James Lees-Milne is flabbergasted by an early encounter with commuters braying into their mobile phones.

One of the pleasures of putting a book like this together was unearthing original responses to supposedly landmark works of art, film or literature. Arnold Bennett, for instance, records being singularly unimpressed by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in his journal and confesses elsewhere to asking T.S.Eliot if The Wasteland was intended as a joke.

Beatrice Webb objects to Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness technique in To the Lighthouse and cockney bookseller Fred Bason leaves the first ‘talking picture’, The Jazz Singer, with a headache complaining that Al Jolson ‘Sings Awfull’ (sic). Filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, meanwhile, took a dislike to Star Wars but, somewhat surprisingly to me, emerges in his diaries as a fan of the 1970s American television series, The Incredible Hulk.

The nation’s changing eating habits can be glimpsed in reports of excursions to Lyon’s Corner House restaurants, Woolworth’s snack counters, Golden Egg fast food outlets and McDonald’s burger bars, left by Sylvia Townsend Warner, Mass Observation’s Gladys Langford, Barbara Pym and Michael Palin. (Palin, after making his first visit to the McDonald’s in Kentish Town on 8 December 1978, notes that bags the food is served in are ‘almost identical in texture, shape and size with the vomit bags tucked in the seat pockets of aircraft’.)

Elsewhere exciting new dishes as ratatouille, turkey risotto and guacamole are sampled by Sally George, Lavina Mynors and Rowena MacDonald in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, respectively.

There is, if anything, nothing more distant than that recent past. What seems like yesterday remains a period when news of Princess Diana’s death reaches my contributors via landline telephone, radio, terrestrial television and inky newsprint (see journalist Anita Sethi’s diary, above) rather than by text, the internet or social media.

Today, of course, people choose to document their lives with pictures on Instagram and comment publicly on events, personal and political, on Facebook or Twitter rather than privately in the leaves of a diary. It will be interesting to see what future historians might then use to construct a similar volume about our current century.